The U-Thong era of Thai Buddhist art, named after the city of U-Thong in present-day Suphan Buri province, refers to a distinct period and style in the history of Thai Buddhist art that flourished during the 13th to 15th centuries. The U-Thong style emerged as a result of the convergence of various artistic influences, particularly those from the Dvaravati, Khmer, and Sukhothai periods. This era is considered significant in the development of Thai Buddhist sculpture and temple architecture, especially for its unique depictions of the Buddha and the evolution of Buddhist iconography in Thailand.

Historical;

The U-Thong era is believed to have developed concurrently with the rise of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya (1351-1767), although its artistic roots can be traced back to earlier periods, particularly the Dvaravati and Khmer civilizations. The city of U-Thong was an important trade and cultural hub, and this facilitated the fusion of various regional and external artistic traditions. As Ayutthaya expanded its influence over neighboring regions, including the former Khmer Empire and Sukhothai, it absorbed various artistic and cultural elements from these regions, contributing to the synthesis of the U-Thong style. This period is seen as a transitional phase in Thai art history, as it helped bridge the gap between earlier Buddhist traditions and the later, more distinct Ayutthaya style.

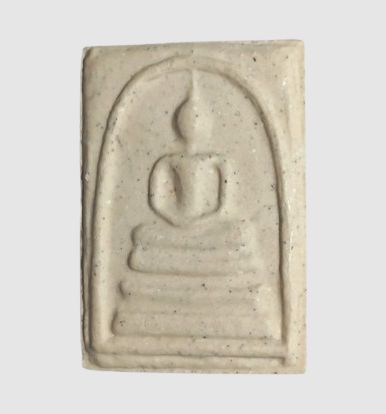

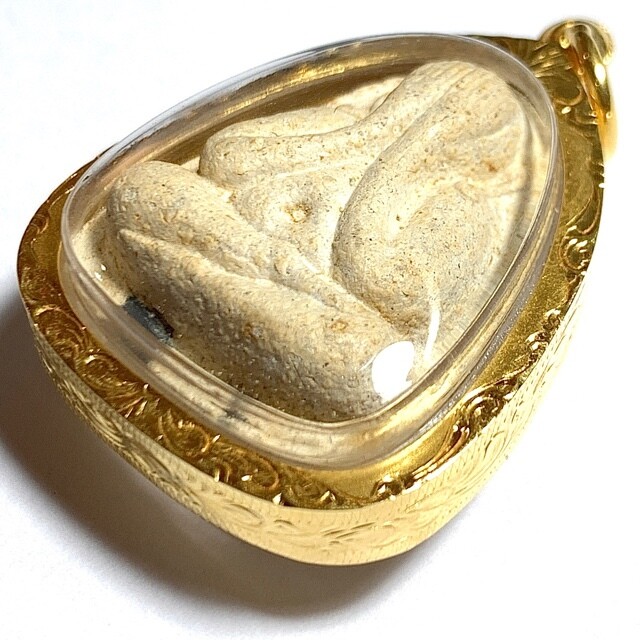

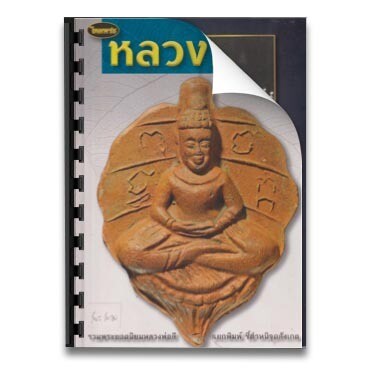

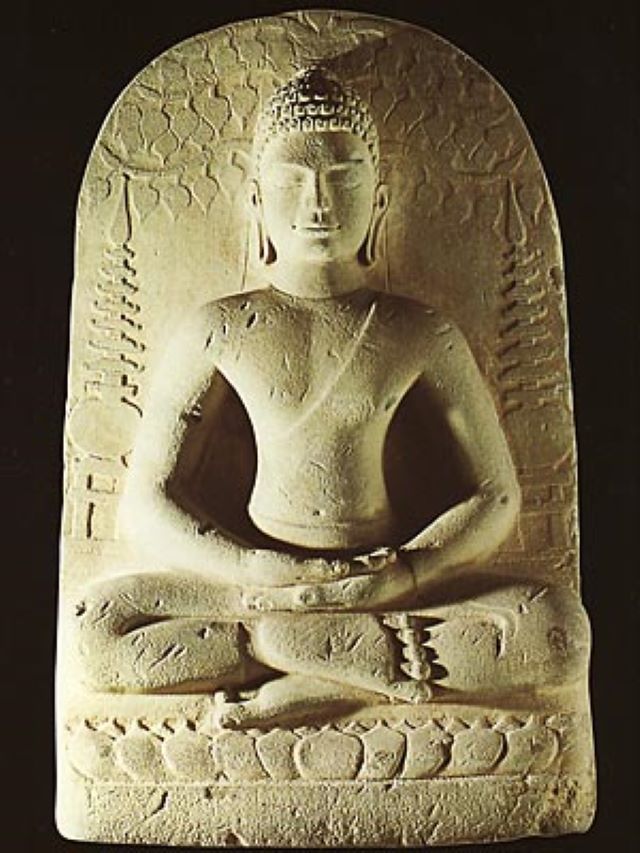

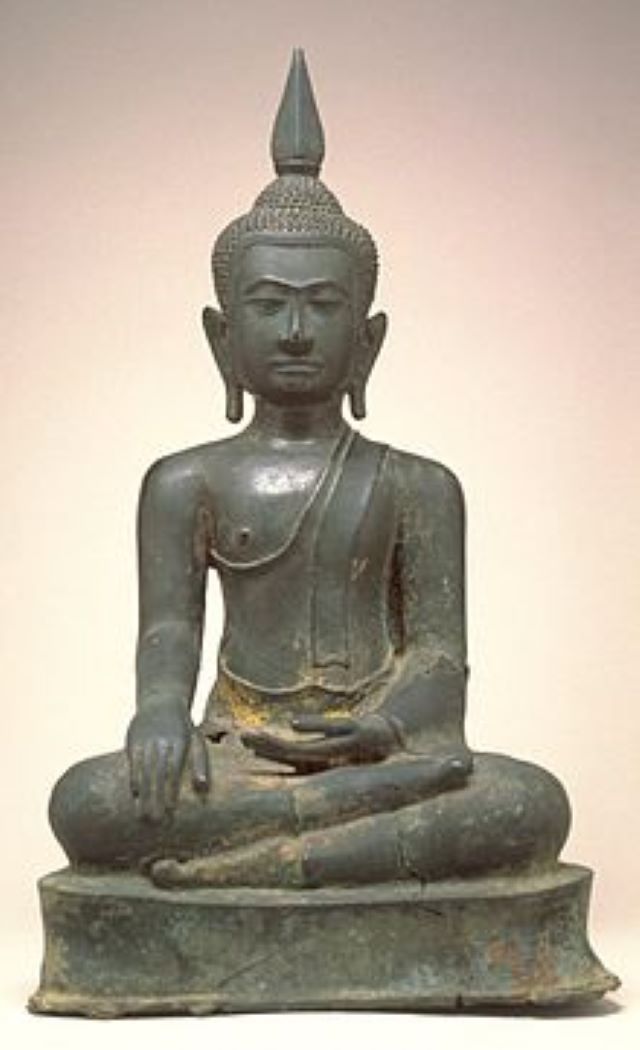

Pra U Tong Buddha Statue

Characteristics of U-Thong Buddhist Art

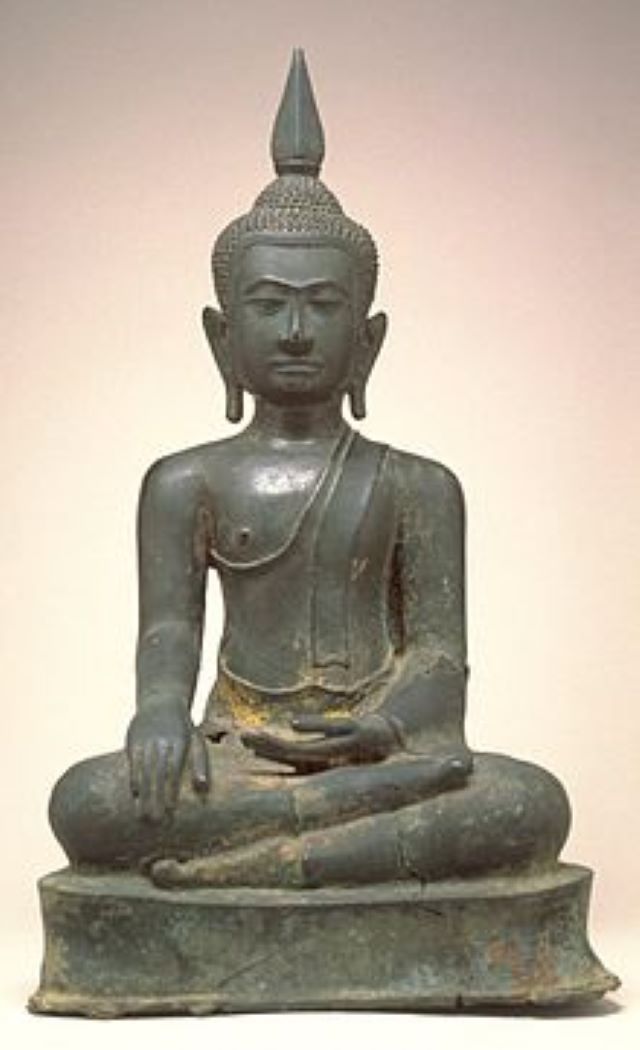

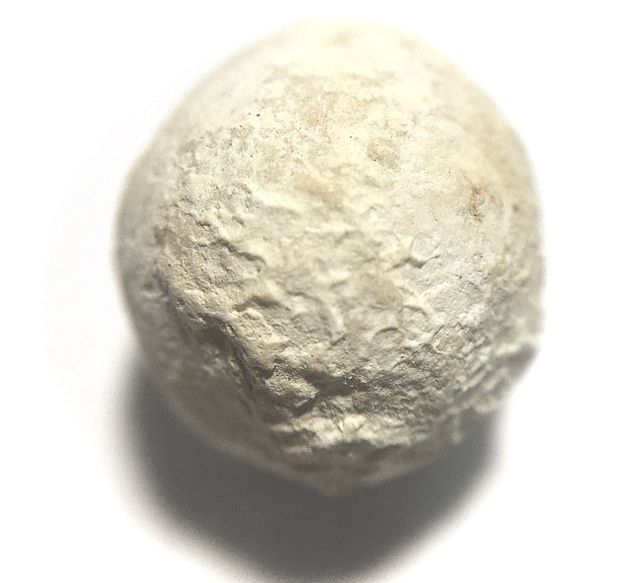

- Buddha Images: The U-Thong era is best known for its Buddha images, which exhibit a blend of Indian, Khmer, and Dvaravati influences. These sculptures are typically cast in bronze, although some stone and stucco images also exist. U-Thong Buddha statues are characterized by:

- Square face: Buddha statues from this era often feature a broad, square-shaped face, with prominent, arched eyebrows and a downward gaze, evoking a sense of calm and introspection.

- Hair and ushnisha: The Buddha’s hair is depicted as tightly curled, often with small, distinct curls. The ushnisha (a protuberance on the top of the head representing wisdom) is usually low and smooth, contrasting with the tall ushnishas seen in later periods like Sukhothai.

- Facial expression: The facial expression is serene, with the eyes half-closed, reflecting deep meditation. The lips are often thin and slightly curved into a subtle smile, embodying the Buddha’s compassion and enlightenment.

- Body proportions: The body of U-Thong Buddha images tends to be stocky and solid, with broad shoulders and a thick torso, which gives a sense of stability and strength.

- Hand gestures (Mudras): U-Thong Buddha images typically depict common hand gestures such as the Bhumisparsha Mudra (touching the earth), symbolizing the Buddha’s moment of enlightenment, or the Abhaya Mudra (fearlessness), signifying protection and reassurance.

- Robes and Drapery: The depiction of the Buddha’s robe in U-Thong art is distinctive. The robe clings closely to the body, with clearly defined lines, giving the figures a sense of gravity and formality. Unlike the Sukhothai style, which often features a transparent, clinging robe, the U-Thong style tends to depict a more structured robe, often covering both shoulders or with one shoulder exposed, depending on the regional variation.

- Influences: The U-Thong style is a synthesis of different artistic traditions:

- Dvaravati: The influence of the earlier Dvaravati period can be seen in the roundness and solidity of the Buddha figures. Dvaravati, an ancient Mon civilization, had already established Buddhist iconography in central Thailand, and its influence continued into the U-Thong era.

- Khmer: Khmer art, especially from the Angkor period, influenced the form and decoration of U-Thong sculptures, particularly in the intricacies of facial features and body proportions.

- Sukhothai: Although U-Thong art predates the full flowering of the Sukhothai style, it overlaps in time, and there are occasional stylistic borrowings. However, the U-Thong Buddha is generally more rigid and formal compared to the fluid grace of the Sukhothai Buddha images.

The Dvaravati era of Thai Buddhist art refers to the artistic and cultural developments during the Dvaravati period, which lasted from approximately the 6th to the 11th century CE. The Dvaravati culture, believed to have been Mon in origin, emerged in the central region of present-day Thailand and was one of the earliest civilizations to establish Buddhism, particularly Theravada Buddhism, in the region. This era is recognized for its significant contributions to the early formation of Thai Buddhist art and religious architecture, laying the foundation for later Thai artistic developments in periods such as Sukhothai and Ayutthaya.

Wat Phra Singh Temple Chiang Saen Era style Thai Buddhist Art form

Historically speaking, Dvaravati was not a unified kingdom in the strict sense, but rather a series of city-states and principalities in the Chao Phraya River basin. These city-states were heavily influenced by Indian culture, which had spread across Southeast Asia through trade, religious missions, and political exchanges. The Mon people, who were instrumental in the development of Dvaravati, adopted Buddhism as their primary religion, particularly Theravada Buddhism, though Mahayana Buddhism and Brahmanism also had an impact on the region.

The Dvaravati culture is known primarily through archaeological remains, inscriptions, and religious monuments, many of which depict early forms of Buddhist iconography. The art produced during this era reflects the syncretism of Indian religious and artistic traditions with local Southeast Asian elements, forming a unique style that is distinct from other regions in the region.

Characteristics of Dvaravati Buddhist Art

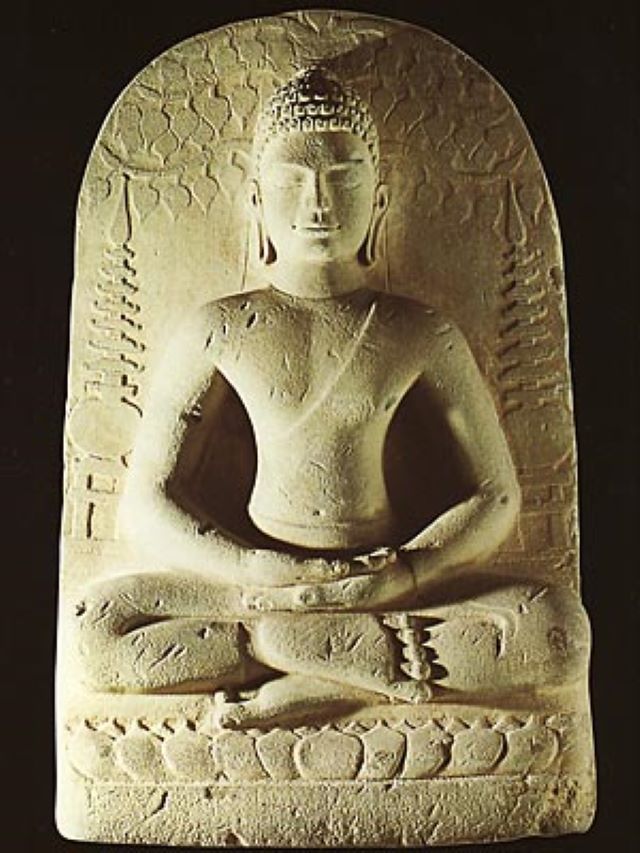

Tvaravadi Buddha in Maravijjaya Mudra

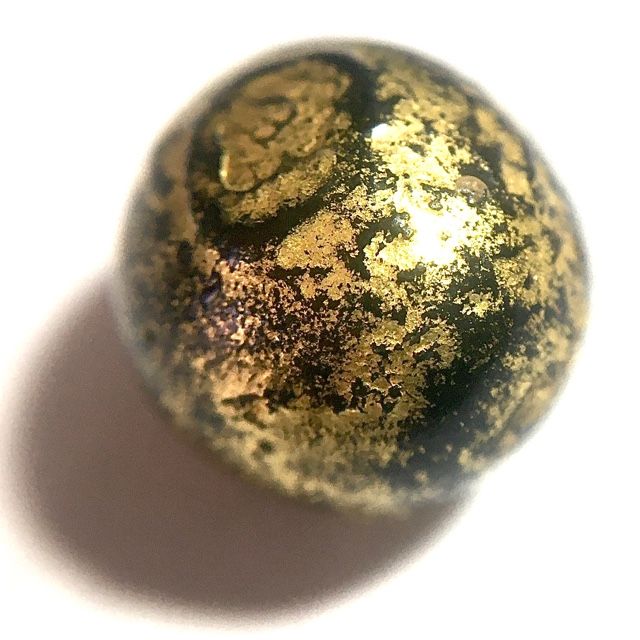

Buddha Images: Dvaravati Buddha images are among the earliest representations of Buddhist iconography in Thailand. These sculptures often show a heavy influence from Indian Gupta and Amaravati art, as well as early Pala art from Bengal. Key features of Dvaravati Buddha images include:

Facial features: The Dvaravati Buddha typically has a rounded face, with a serene expression, and large, almond-shaped eyes. The eyebrows are arched, and the nose is prominent but rounded. The facial expressions often exude calm and peacefulness, reflecting the meditative state of the Buddha.

Hair and ushnisha: The Buddha’s hair is usually depicted in small, tight curls, and the ushnisha (a cranial protuberance symbolizing the Buddha’s wisdom) is prominent but simple.

Body proportions: Early Dvaravati Buddha images tend to have heavy, stocky proportions, with broad shoulders and a thick torso, giving the figures a sense of solidity and permanence.

Hand gestures (Mudras): The Bhumisparsha Mudra (touching the earth) is commonly depicted in Dvaravati Buddha images, symbolizing the Buddha’s moment of enlightenment. Other common mudras include the Dhyana Mudra (meditation gesture) and the Abhaya Mudra (gesture of fearlessness).

Materials and Techniques: Most Dvaravati Buddha images are made of bronze, stucco, or stone. These materials were locally sourced, and the techniques used in their creation demonstrate a blend of local craftsmanship with Indian artistic traditions. Bronze casting was particularly advanced during this period, and many surviving examples of Dvaravati art showcase intricate detailing and a high level of technical skill.

Symbolism: Dvaravati art is deeply symbolic, reflecting core Buddhist principles such as the impermanence of life (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and non-self (anatta). These themes are subtly expressed through the serene and meditative postures of the Buddha figures, as well as in the religious narratives depicted in reliefs and stupas.

Tvaravadi Era Buddha Heads

Stupas and Religious Architecture

The Dvaravati era saw the construction of numerous stupas (Buddhist reliquary structures), which were central to the religious life of the period. These stupas served as places for devotion, housing sacred relics of the Buddha or important monks. Dvaravati stupas typically follow a simple design, with a hemispherical dome (anda) sitting on a square base, which was often elaborately decorated with carvings and reliefs.

Specific features of Dvaravati stupas:

Stupa Shape: The dome shape of Dvaravati stupas resembles early Indian models, reflecting the influence of Indian Buddhist architecture. However, local innovations were also evident, such as the addition of tiers and terraces surrounding the main stupa.

Decorative Reliefs: Many stupas were decorated with narrative reliefs that depicted scenes from the Jataka tales (stories of the Buddha’s past lives) or events from the Buddha’s life. These reliefs were intricately carved into stucco or stone and showcased both religious and artistic significance.

Phra Pathom Chedi

One of the most famous Dvaravati stupas is the Phra Pathom Chedi in Nakhon Pathom, considered one of the oldest and largest stupas in Thailand. It has been rebuilt and renovated over the centuries, but its origins date back to the Dvaravati period. Phra Pathom Chedi, located in Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, is considered the world’s tallest stupa and holds great significance as it marks the site where Buddhism was first introduced to Thailand. Its name translates to “the first chedi,” symbolizing the beginning of the Buddhist faith in the region. The chedi serves as a major pilgrimage site for Buddhists and represents both historical and spiritual importance in Thai culture. It is recognized as the world’s tallest stupa, standing at 127 meters. Its construction dates back to the 19th century, initiated during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV) in 1853. The chedi was built to commemorate the introduction of Buddhism to Thailand and to restore the ancient stupa that existed on the site.

The construction involved traditional methods and local materials, primarily bricks and mortar. The design reflects a blend of Indian and Thai architectural styles, with a large circular base and a tapering dome. The project was overseen by various architects and craftsmen, including the famous Italian architect, who contributed to its grandeur. In 1870, after 17 years of construction, Phra Pathom Chedi was completed and consecrated. It serves not only as a religious site but also as a symbol of Thai cultural heritage and the historical significance of Buddhism in the region. Today, it attracts numerous visitors and pilgrims from around the world.

Narrative Reliefs and Decorative Art

In addition to Buddha images and stupas, the Dvaravati period is known for its decorative art, especially its narrative reliefs. These reliefs, often found on the walls of stupas and temple structures, depict key events from the Buddha’s life, such as his birth, enlightenment, and the first sermon at Sarnath.

One unique aspect of Dvaravati reliefs is the depiction of the Buddha using symbolic forms. In early Indian and Dvaravati art, it was common to represent the Buddha not in human form, but through symbols such as the Bodhi tree (symbolizing enlightenment), the footprint (symbolizing the Buddha’s presence on Earth), or the wheel (representing the Dhamma or Buddha’s teachings). Over time, these symbolic representations gave way to more anthropomorphic depictions, though they remained an important part of Dvaravati artistic tradition.

In addition to Buddhist themes, the Dvaravati period also produced reliefs and carvings that reflected Brahmanical (Hindu) influence, depicting Hindu deities such as Vishnu and Shiva. This highlights the religious syncretism of the period, with Brahmanism and Mahayana Buddhism coexisting alongside the dominant Theravada tradition.

Influence on Later Thai Art

The Dvaravati period laid the groundwork for much of the religious and artistic development in Thailand in subsequent centuries. The themes, techniques, and forms developed during the Dvaravati era were passed down to later periods, including the Sukhothai and Ayutthaya kingdoms.

For example, the Bhumisparsha Mudra, prominent in Dvaravati Buddha images, remained a key element in later Thai Buddha sculptures. The rounded, solid form of the Dvaravati Buddha also influenced the more graceful and refined images of the Buddha seen in the Sukhothai period, where a new emphasis on fluidity and elegance in religious art emerged.

The architectural styles of the Dvaravati period, especially in the design of stupas, also influenced later Thai Buddhist architecture. Many of the stupas and chedis constructed during the Sukhothai and Ayutthaya periods retained the tiered and terraced designs first seen in Dvaravati architecture, though these later structures became more elaborate and ornate.

Conclusion

The Dvaravati era is a pivotal period in the history of Thai Buddhist art, representing the earliest phase of Buddhist artistic expression in Thailand. It is marked by its synthesis of Indian and local traditions, creating a unique style that reflected the religious and cultural dynamics of the time. The art and architecture of this period not only served religious functions but also helped establish the foundational visual vocabulary of Thai Buddhist art for centuries to come.

Through its Buddha images, narrative reliefs, and religious architecture, the Dvaravati era made lasting contributions to the Buddhist artistic heritage of Thailand. Even today, the influence of this period can be seen in the religious practices, artistic traditions, and cultural identity of the Thai people.

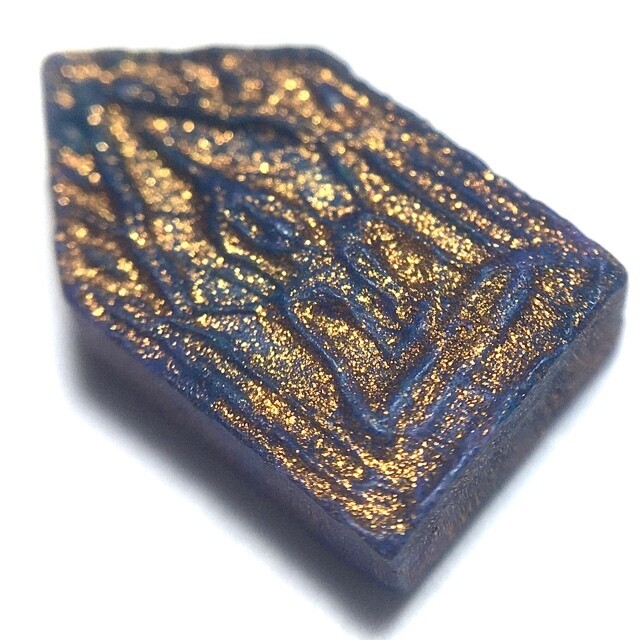

U-Thong Temple Architecture

In addition to Buddha images, the U-Thong period also saw developments in temple architecture. U-Thong temples typically feature elements that reflect a combination of Dvaravati and Khmer styles. For instance, chedis (stupas) from this period are often square at the base with tapering forms, resembling early Khmer temples. Some of these structures were influenced by the classical Khmer design of prasats (sanctuaries) but were adapted to the specific Buddhist context of Thailand.

These temples were often decorated with stucco reliefs and Buddha images, many of which have survived to the present day. The architectural forms from this era laid the groundwork for the more complex and elaborate structures seen during the Ayutthaya period, which followed the U-Thong era.

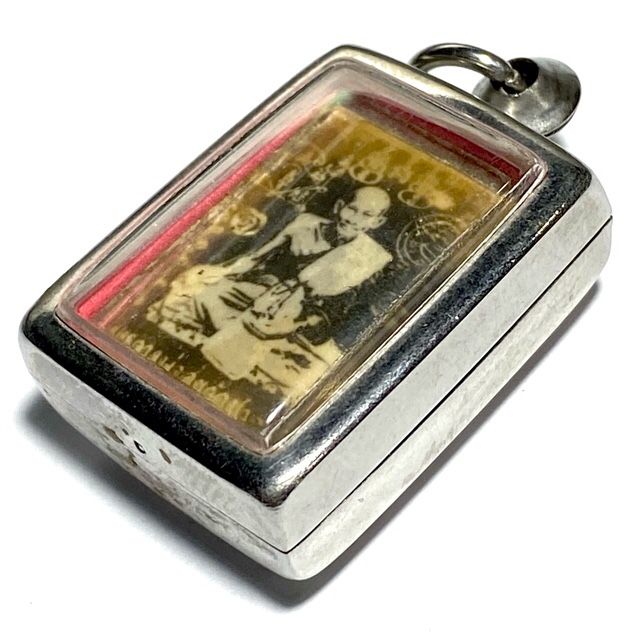

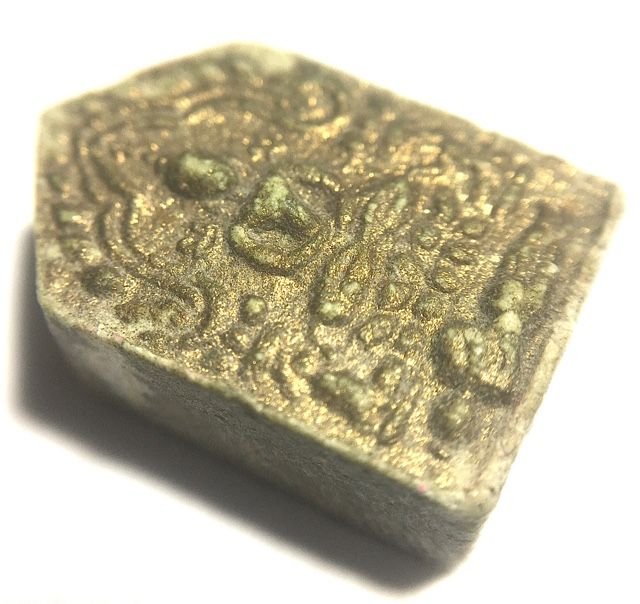

Cultural and Religious Significance

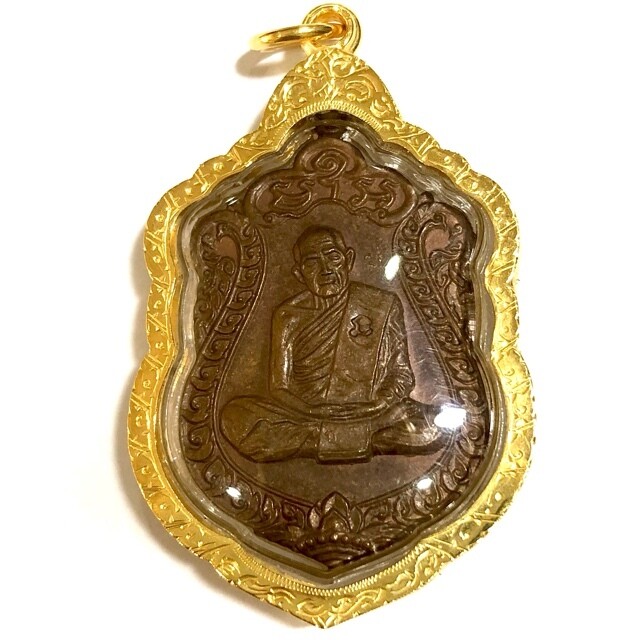

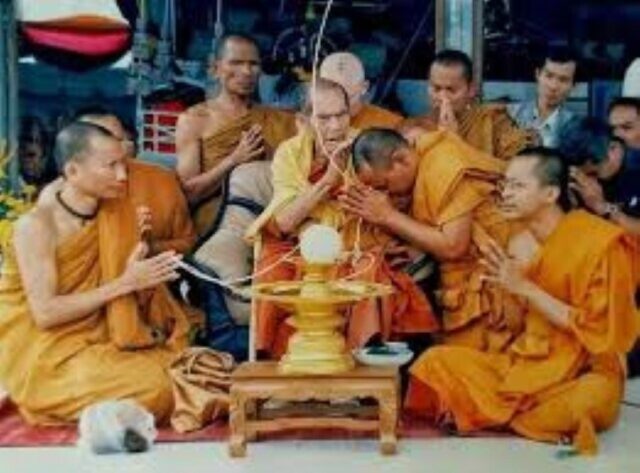

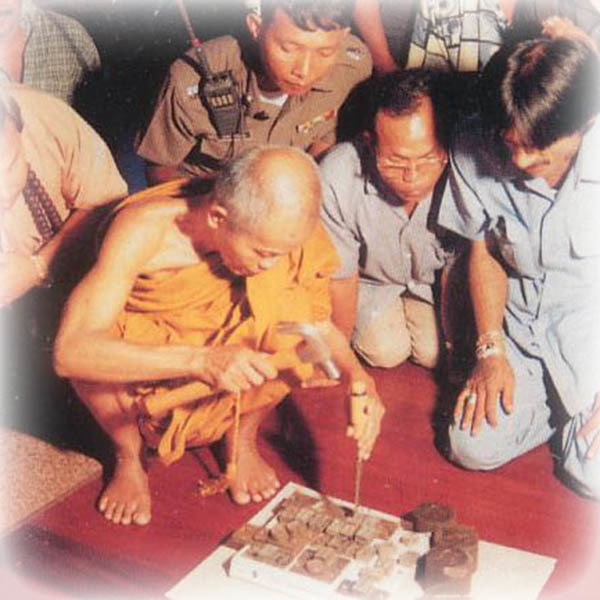

The U-Thong period is a reflection of the eclectic nature of Thai art, which absorbed and integrated elements from different regions and periods into a uniquely Thai interpretation of Buddhist iconography. The Buddha images from this era were not just objects of worship but also served as cultural symbols representing the consolidation of Buddhist influence in Thailand, particularly during the rise of the Ayutthaya Kingdom.

In a religious context, U-Thong amulets and Buddha images were believed to provide protection and bring good fortune. Many of these artifacts were created as part of merit-making activities, with donors commissioning the creation of Buddha statues or the construction of temples to gain spiritual merit. Today, U-Thong Buddha images are still revered, and the style remains influential in Thai religious art, particularly in central Thailand. The U-Thong era, most definitely marks an important phase in the history of Thai Buddhist art, characterized by its synthesis of various artistic traditions and its contributions to the development of Buddhist iconography in Thailand. Its distinctive Buddha images, marked by square faces, serene expressions, and carefully detailed robes, remain among the most iconic representations of Buddhist art in Southeast Asia. The U-Thong style laid the foundation for the later artistic developments of the Ayutthaya period, continuing to influence Thai Buddhist art well into the future.