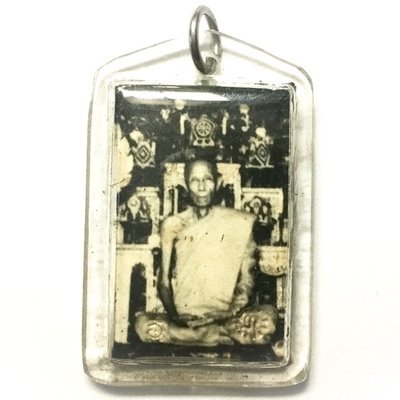

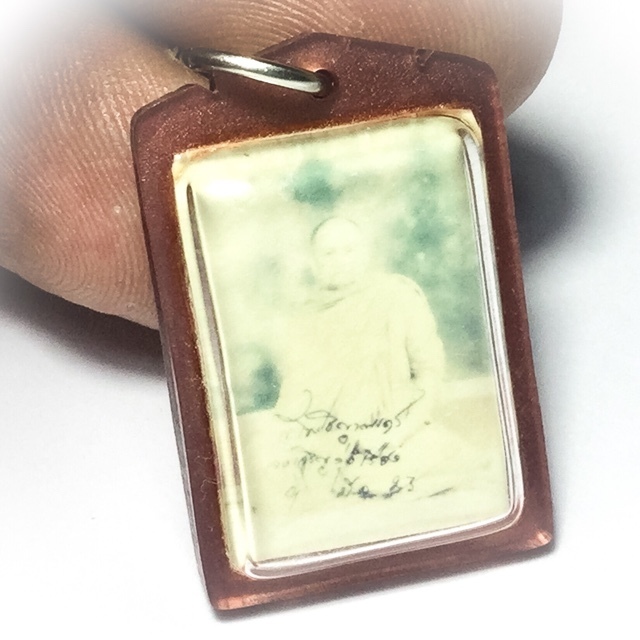

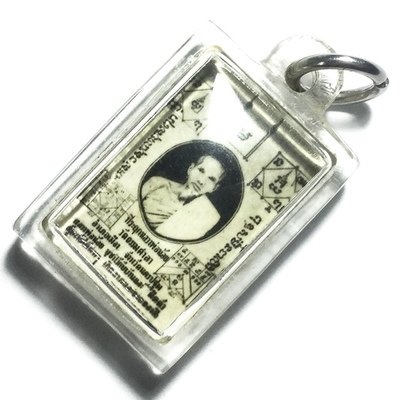

Presenting a tiny but powerful and rare classic amulet from one of the Great Khao Or Masters of the 20th Century, Rian Glom Lek Hlang Chedi 2505 BE Nuea Tong Daeng Miniature Guru Monk Coin Por Tan Klai Wajasit

This Sacred amulet of the Great Khao Or Master of Nakorn Sri Tammarat, Master of Wat San Khan and Wat Pratat Noi, is a very rare amulet from Por Tan Klai’s 2505 BE Blessing Ceremony Edition, and is considered a ‘Jaek mae Krua’ type amulet (meaning ‘give to the kitchen maids and temple helpers’), which is suitable not only for men, but due to its miniature size, a perfect amulet for ladies or children to wear.

Rian Glom Lek 2505 BE Por Tan Klai Wajasit Wat Suan Khan

The 2505 BE edition of amulets of Por Tan Klai, is a highly preferred edition, which saw his famous ‘Rian Glom’ round Monk coin amulet with Chakra released, The Rian Glom Lek Hlang Chedi, and the Roop Tai Por Tan Klai Guru Monk Blesséd Photographamulets such as look om chan hmak and ya sen tobacco balls, and sacred powder amulets of various models.

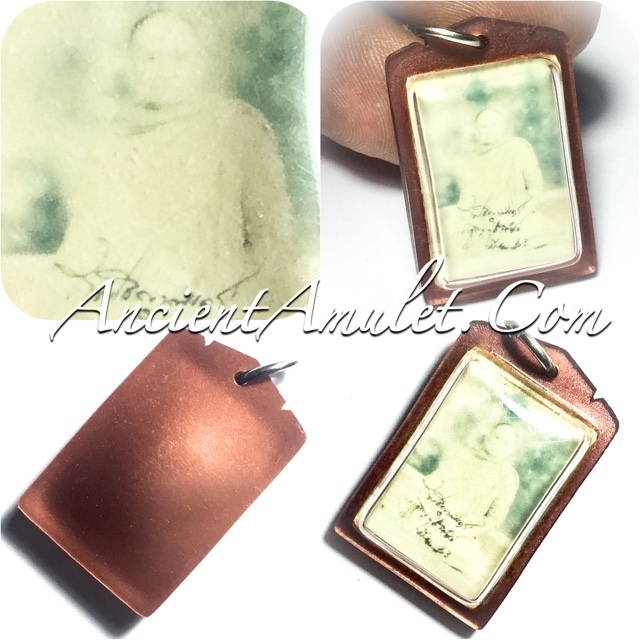

A very rare and highly prized amulet for the devotees of Por Tan Klai to associate with his image and pray to him with a blessed image of the Guru, and the Chedi Relic Stupa on rear face for Buddhanussati and Marananussati. A powerful and Sacred amulet which has passed through the hands of the Guru and been blessed by him.

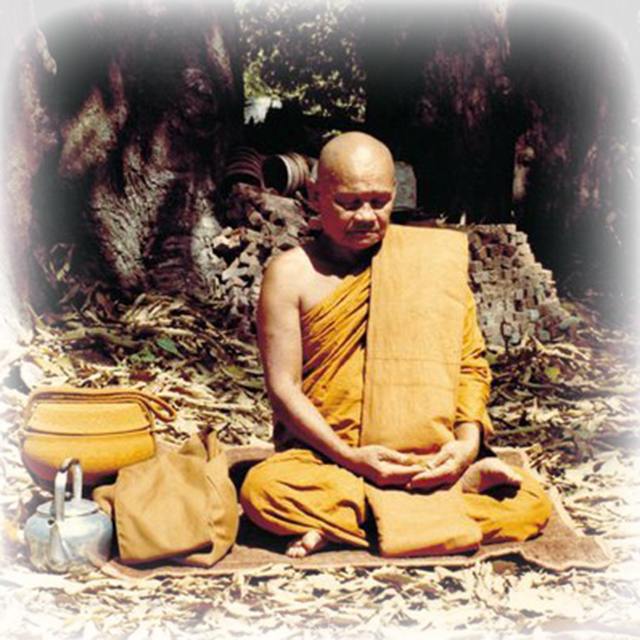

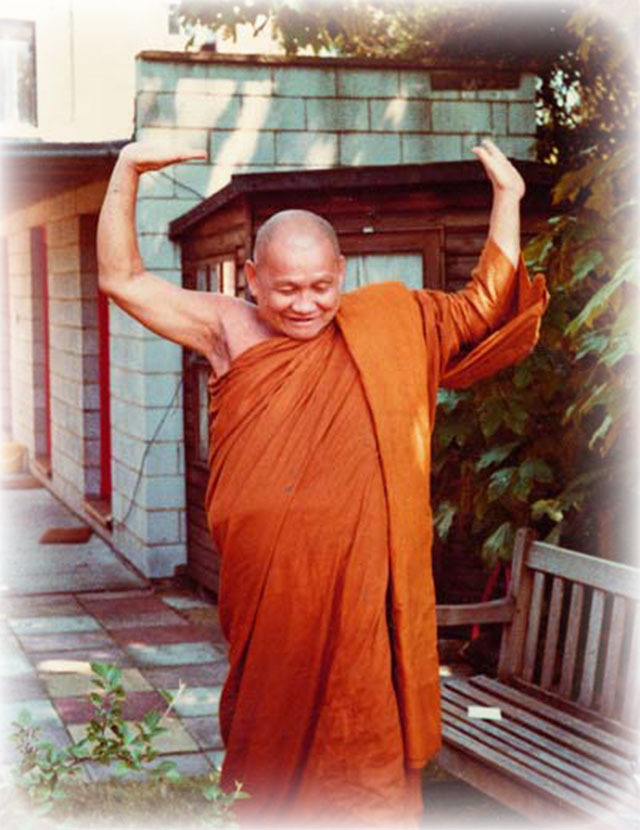

Por Tan Klai was one of the Top Guru Master Monks of the Last Century, and is considered one of the Four Great Masters of the Previous Generation of Lineage Masters of the Khao Or Southern Sorcery Lineage.

Kata Bucha Por Tan Klai

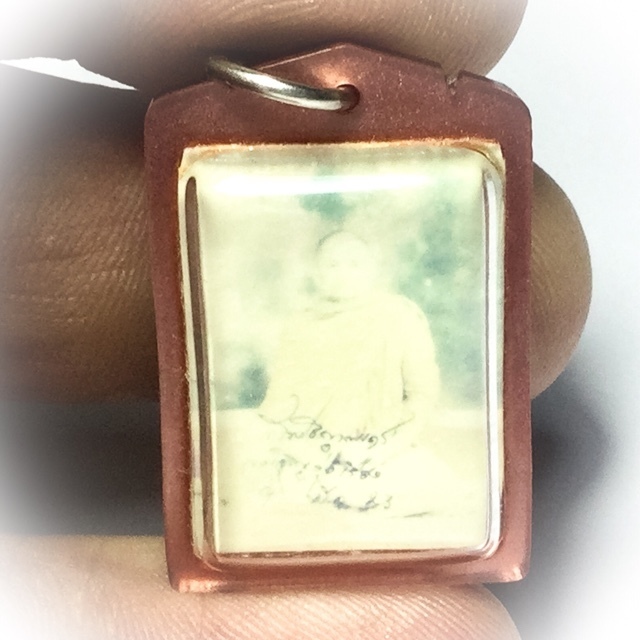

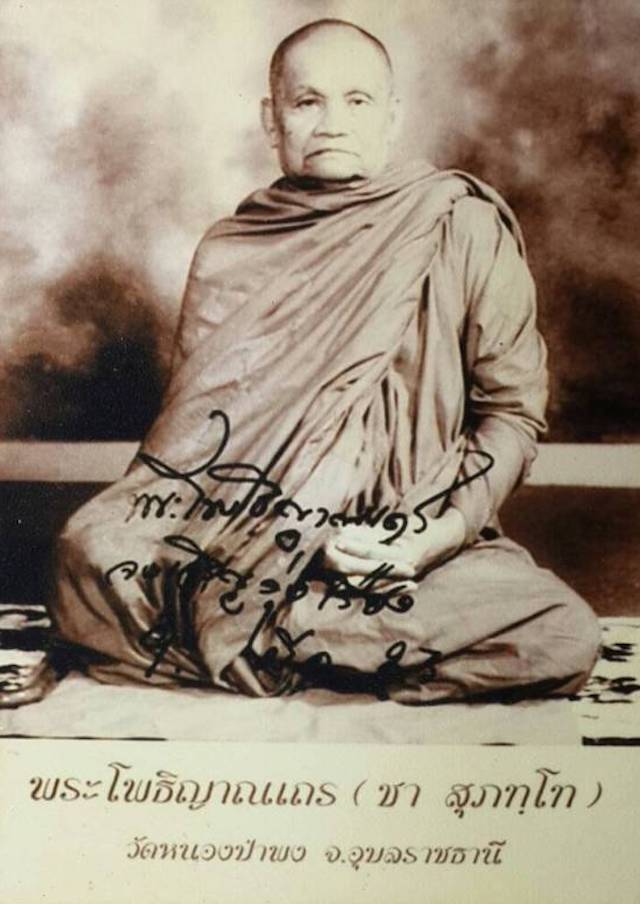

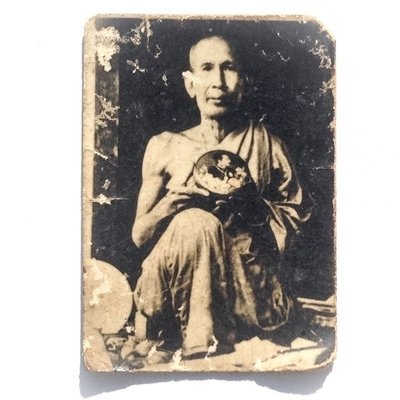

Roop Tai Khaw Dam Gradat Hnang Gai 2520 BE Ajahn Chah Supatto Wat Nong Pha Pong

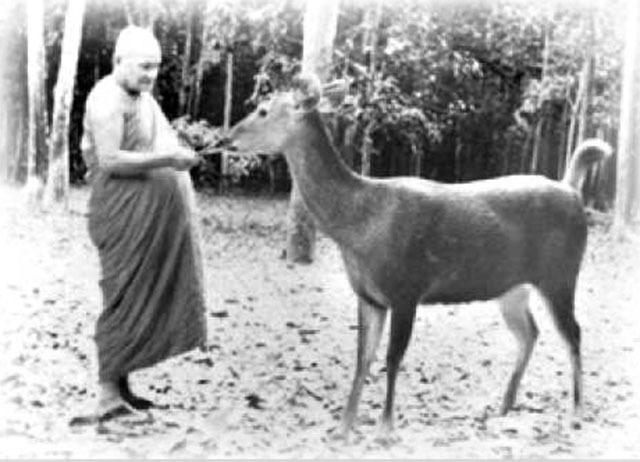

Roop Tai Khaw Dam (Monochrome Photograph in 'Chicken Skin' textured photographic paper, of the great deceased Kroo Ba Ajarn Luang Phu Ajarn Chah Supatto, of Wat Nong Pha Pong, in Ubon Rachatani. Released in 2520 BE, this Sacred Blesséd Guru Monk Photo is a very rare acquisition indeed, from the Highly revered Arya Sangha attained Master, Luang Phu Ajarn Chah Supatto, of Wat Nong Pha Pong.

Ajarn Chah was a great Kroo Ba Ajarn Master Guru Monk who is known to have hardly ever made amulets at all, for his practice was that of a Tudong Forest Monk. The amulet is very rare due to the fact that most of them have already found their owners, who are devout followers of Ajarn Chah. Considering how few amulets Ajarn Chah made, and how many devotees he has around the world, it is not surprising how rare his amulets are to find in the present era.

Some people believe that Ajarn Chah never made any amulets at all, but this is a Fallacy. He does have a pantheon of amulets, but they are less extensive and much less heard of than those of other masters, for he did not advertise the fact very much nor did he produce many after his name became international news, as he became the first Thai Buddhist Master to bridge the gap between east and west, despite many foregoers, as he received and managed to communicate the Dhamma to the first serious practitioners who began to arrive from the West.

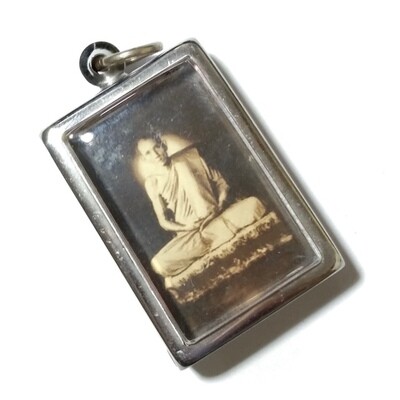

Ajarn Chah (From Wikipedia)

Ajarn Chah Supatto, was an influential teacher of the Buddha-Dhamma, and a founder of two major monasteries in the Thai Forest Tradition.

Respected and loved in his own country as a man of great wisdom, he was also instrumental in establishing Theravada Buddhism in the West. Beginning in 1979 with the founding of Cittaviveka (commonly known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery) in the United Kingdom, the Forest Tradition of Ajarn Chah has spread throughout Europe, the United States and the British Commonwealth.

The Dhamma talks of Ajarn Chah have been recorded, transcribed and translated into several languages. More than one million people, including the Thai royal family, attended Ajarn Chah's funeral in January 1993held a year after his death due to the "hundreds of thousands of people expected to attend". He left behind a legacy of dhamma talks, students, and monasteries.

Ajarn Chah was born on 17 June 1918 near Ubon Ratchathani in the Isan region of northeast Thailand. His family were subsistence farmers. As is traditional, Ajarn Chah entered the monastery as a novice at the age of nine, where, during a three-year stay, he learned to read and write. He left the monastery to help his family on the farm, but later returned to monastic life on 16 April 1939, seeking ordination as a Theravadan monk (or Bhikkhu).

According to the book Food for the Heart: The Collected Writings of Ajarn Chah, he chose to leave the settled monastic life in 1946 and became a wandering ascetic after the death of his father.

He walked across Thailand, taking teachings at various monasteries. Among his teachers at this time was Ajarn Mun, a renowned meditation master in the Forest Tradition. Ajarn Chah lived in caves and forests while learning from the meditation monks of the Forest Tradition.

For the next seven years Ajarn Chah practiced in the style of an ascetic monk in the austere Forest Tradition, spending his time in forests, caves and cremation grounds. He wandered through the countryside in quest of quiet and secluded places for developing meditation. He lived in tiger and cobra infested jungles, using reflections on death to penetrate to the true meaning of life.

During the early part of the twentieth century Theravada Buddhism underwent a revival in Thailand under the leadership of outstanding teachers whose intentions were to raise the standards of Buddhist practise throughout the country. One of these teachers was the Venerable Ajarn Mun Bhuridatta. Ajarn Chah continued Ajarn Mun's high standards of practise when he became a teacher.

The monks of this tradition keep very strictly to the original monastic rule laid down by the Buddha known as the vinaya. The early major schisms in the Buddhist sangha were largely due to disagreements over how strictly the training rules should be applied. Some opted for a degree of flexibility (some would argue liberality) whereas others took a conservative view believing that the rules should be kept just as the Buddha had framed them.

The Theravada tradition is the heir to the latter view. An example of the strictness of the discipline might be the rule regarding eating: they uphold the rule to only eat between dawn and noon. In the Thai Forest Tradition monks and nuns go further and observe the 'one eaters practice', whereby they only eat one meal during the morning.

This special practice is one of the thirteen dhutanga - optional ascetic practices permitted by the Buddha that are used on an occasional or regular basis to deepen meditation practice and promote contentment with little. They might, for example, as well as eating only one meal a day, sleep outside under a tree, or dwell in secluded forests or graveyards.

After years of wandering, Ajarn Chah decided to plant roots in an uninhabited grove near his birthplace. In 1954, Wat Nong Pah Pong monastery was established, where Ajarn Chah could teach his simple, practice-based form of meditation. He attracted a wide variety of disciples, which included in 1966, the first Westerner, Venerable Ajarn Sumedho.

Wat Nong Pah Pong includes over 250 branches throughout Thailand, as well as over 15 associated monasteries and ten lay practice centers around the world.

In 1975, Wat Pah Nanachat (International Forest Monastery) was founded with Ajarn Sumedho as the abbot. Wat Pah Nanachat was the first monastery in Thailand specifically geared towards training English-speaking Westerners in the monastic Vinaya, as well as the first run by a Westerner.

In 1977, Ajarn Chah and Ajarn Sumedho were invited to visit the United Kingdom by the English Sangha Trust who wanted to form a residential sangha. 1979 saw the founding of Cittaviveka (commonly known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery due to its location in the small hamlet of Chithurst) with Ajarn Sumedho as its head.

Several of Ajarn Chah's Western students have since established monasteries throughout the world. By the early 1980s, Ajarn Chah's health was in decline due to diabetes. He was taken to Bangkok for surgery to relieve paralysis caused by the diabetes, but it was to little effect.

Ajarn Chah used his ill health as a teaching point, emphasizing that it was "a living example of the impermanence of all things...(and) reminded people to endeavor to find a true refuge within themselves, since he would not be able to teach for very much longer". Ajarn Chah would remain bedridden and ultimately unable to speak for ten years, until his death on January 16, 1992 at the age of 73

A VIDEO BIOGRAPHY SERIES OF THE LIFE OF AJARN CHAH